D-46 Vendée Globe: Making life on board bearable

ROAD TO THE VENDÉE GLOBE #1: In the first of a series of preview articles in the lead-up to the Vendée Globe start on November 8, Ed Gorman looks at the issue of comfort – and discomfort – on board an IMOCA.

The IMOCA fleet has a deserved reputation for exceptional performance, for spectacular displays of awesome speed and power, but it also for being made up of some of the most hostile racing platforms ever used in world sailing.

Even before the advent of foiling, the wide and flat hull form and super-light carbon hulls of the IMOCA boats were making them extremely uncomfortable, especially going upwind and racing in the breeze. The foiling revolution has only made the violent, noisy and wet experience on board even more difficult for their lone skippers.

Britain’s Sam Davies, skipper of Initiatives Coeur, says that when outsiders sail on her boat it reminds her that IMOCA sailors have got used to conditions on board that few others would tolerate. “It seems to be that the boats are very unbearable for anyone other than IMOCA skippers,” she said.

© Sam Davies/Initiatives-coeur

© Sam Davies/Initiatives-coeur

So what have her fellow Vendée Globe competitors been doing to try to make life on board a bit more comfortable as they prepare for more that 70 days alone around the world and some of the worst weather the planet has to offer?

Boris Herrmann says the most important change he and his team have made on SeaExplorer-Yacht Club de Monaco since her Gitana days has been the addition of a “pilot seat” that sits sideways to the boat’s fore an aft axis and can tilt as the boat heels.

“It supports my back and my head can lean against it – and you can lean on it and just observe the boat sailing along and keep an aye on the radar and the alarms. It is quite close to the entrance to the cockpit so I can jump out of the seat very quickly,” he said.

© Boris Herrmann/Team Malizia

© Boris Herrmann/Team Malizia

The German sailor takes his meals there too. “I can sit there and eat and when the boat moves a lot when it is going fast, that is just the best place to be supported –and you don’t need much effort to hold on.”

Like many of his fellow IMOCA skippers, Herrmann has also modified the cockpit to enclose it at the back with a curtain that keeps the weather and the water out. “We are keeping the cockpit entirely closed so it is nice and dry and you can come out in your pyjamas if you want and not get wet,” he said.

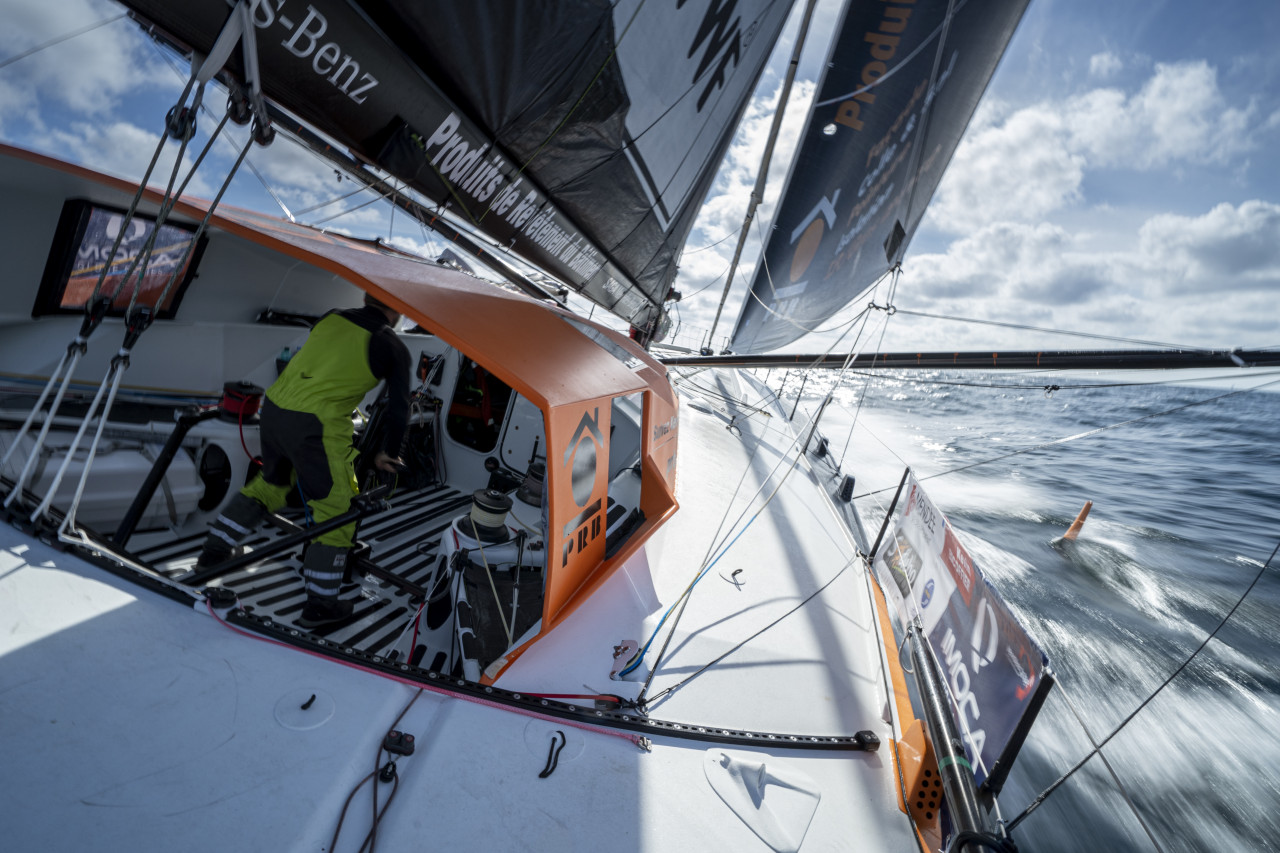

His French rival Kevin Escoffier on the much-modified PRB has made a similar change with the same objective. “(Enclosing the cockpit) adds to comfort but also speed because without a roof you have 100 kilos of water in the cockpit and when you don’t have that, the boat is lighter and faster,”he said.

© Yann Riou / polaRYSE

© Yann Riou / polaRYSE

Escoffier has been using ear-plugs on board to try to ameliorate the impact on his senses of the constant crashing and banging as the boat flies and falls off waves, as he says, “like a plank of wood being slapped on the water.”The Frenchman who has already sailed round the world three times, is using plugs molded to his ear and with filters so he can control how much sound is dampened.

“I don’t want to be completely cut-off from the sounds of the boat,”he explained. “You can do that with noise cancellers but, after that, you don’t hear anything of the boat. For me it is very important to hear because, by the sounds of the boat, you can tell if you have broken something and you can hear the aerodynamic noise so you can tell if something’s not right.”

Herrmann likes to hear the full sound scape of his IMOCA when his boat is rocking along at speed. “Sometimes I like to hear the screaming of the foil because it sounds fast and you are happy about it,”he said. “Then it can get too much and you just try to avoid it with the ear plugs.”

© Yann Riou / polaRYSE

© Yann Riou / polaRYSE

Ear defenders aren’t the only things Escoffier will wear to protect himself on board. The 40-year-old skipper from St Malo has been testing rugby clothing to help protect his body from impacts when getting thrown about in the cockpit and down below on PRB. “Last week I tried some rugby stuff for my back and legs,” he said. “It can help protect me if I get thrown around…and now I wear a rugby helmet which is quite light and warm so, when it is cold, it is also a good thing from that perspective.”

Trying to sleep on board is a major challenge in such an unstable, noisy and violent environment. Herrmann’s team has added specially developed mattresses to improve comfort on his two bunks and curtains around them that help him to sleep during the day.

Escoffier, meanwhile, has been working with a doctor who specialises in sleep and his preparation has focused on trying to establish a sleeping position – on a specially developed mattress – where his body is as stable as possible, to help replenish his mental energy. “During the first minutes when you sleep, it is the body that is getting energy back,”he said. “But the brain is not recovering its energy to stop you going crazy. For that you need the body not to move too much during this part of the sleeping phase, so the mattress we have on board does not move too much from side to side.”

The psychology of surviving the solo IMOCA experience is a big part of the challenge. Herrmann has been working with a sports psychologist and they have used techniques like seeing things from the outside – the so-called “helicopter view” – and changing perspectives to help stay in a positive frame of mind.

Herrmann has found that being in contact with friends on shore is a great way to stay motivated and avoid periods of loneliness. On the Vendee-Arctique-les Sables d’Olonne Race he kept in touch with friends though a new What’s App group. “Being shut off from the outside world feels so unnatural because we are so highly connected nowadays,”he said. “So being connected helped me a lot – I didn’t expect it – but I really like it,” he said.

Escoffier has been working with Alexis Landais, a sports psychologist he first got to know as a member of Dongfeng Race Team in the last Volvo Ocean Race. The two points they have been focusing on are how to take the right decisions even when you are exhausted, and learning how to sail the boat at a level that is sustainable when single-handed on a circumnavigation.

“It’s about adjusting the level of performance,”he said. “It’s a long race and you must not sail it like a Jacques Vabre or an Azimut 48-hour race. It is about learning how to be confident in the way you will adjust the percentage of performance you will use on the boat in the Vendée Globe.”

Teams info

The Transat CIC: A new beginning for Bellion and a return to solo racing for Pedote

For Éric Bellion The Transat CIC, which starts from Lorient bound for New York on Sunday, is a huge moment in his journey to this year’s Vendée Globe.

•••ALL ACCESS #3 with Sam Davies

This week, we boarded the IMOCA Initiatives-Cœur with Sam Davies for a 24-hour training session. The objective was to sail in a fleet, alongside the Pôle Finistère Course au Large, and to familiarize ourselves with solo …

•••