Marcel Van Triest: It’s your choice – head north or try the south

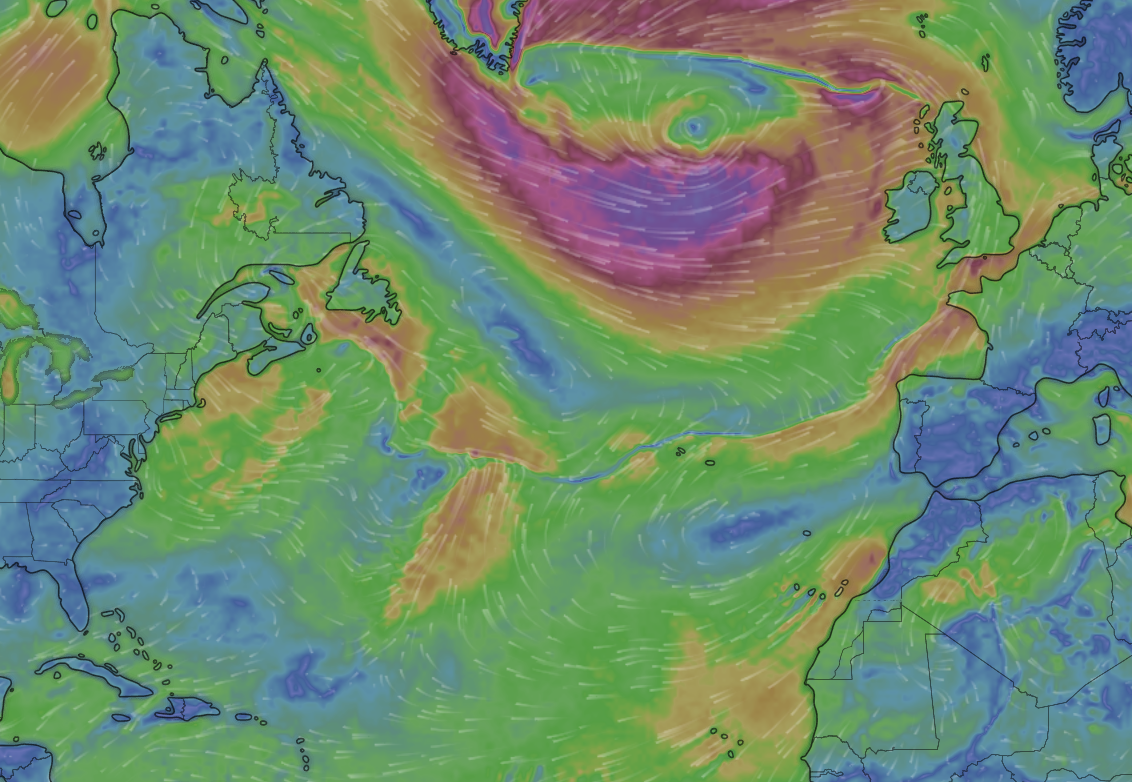

As the 40 IMOCA teams in the Transat Jacques Vabre-Normandie Le Havre face their first night at sea, after one of the most spectacular race starts in recent memory, they will be thinking through the biggest strategic decision of the race – whether to go north or south on the long road to Martinique.

This classic biennial contest is happening later in the year than ever before and it comes on the back of a turbulent autumnal weather picture in the north Atlantic, two ingredients that are making decisions on weather and routing particularly challenging.

We checked in with Marcel Van Triest the leading meteorologist who has been advising four teams in the build-up to this race in the IMOCA Class (weather routing after the start is forbidden).

His customers are four of the top boats in the fleet – Jérémie Beyou and Franck Cammas on Charal, the early pace-setter, Justine Mettraux and Julien Villion on Teamwork, Sam Goodchild and Antoine Koch on For The Planet and defending Transat Jacques Vabre champion Thomas Ruyant sailing with Morgan Lagravière on For People.

Van Triest simplifies the complex and fast moving weather picture in terms of a northerly option in the early stages, that will see skippers dealing with a succession of depressions and a lot of upwind sailing, and a southerly route that will be kinder on boats and sailors but could be much slower.

Here’s the southern option first, the efficacy of which will depend on how a high pressure system centred to the southwest of Lisbon develops in the coming days. To start with all the boats will cross a frontal system off Ushant as they beat down the English Channel. Then it will be decision time.

© © Jean-Marie Liot / Alea

© © Jean-Marie Liot / Alea

“If they choose the southerly route, they will bear off and head for Cape Finisterre and try to get across to the south before it closes down,”explained van Triest. “There’s a high that becomes a ridge. While it’s a high, you can actually get around it – there is some flow around it – whereas afterwards it just becomes a ridge and a whole lot of nothing. So it’s closing down the window there and it’s already extremely uncertain if they can get across. They will end up close to the Moroccan coast or the Canary Islands.”

This option also involves longer term uncertainty: “The danger is the boats that go south will have to invest quite a lot to get across there,” added van Triest. “There will be a passage with very light airs, dead downwind, gybing down towards the south, and you have to keep on going south until you are in the tradewinds. Once you are in them, you will have wind, but then you are pretty much dead downwind all the way to Martinique, so it’s not extremely fast.”

© © Jean-Marie Liot / Alea

© © Jean-Marie Liot / Alea

The northerly option is another kettle of fish entirely with less sun, more cold water on deck and a rougher ride. “On this route you’ve got a sequence of lows to deal with, which is not very enticing, unless you are a sucker for punishment,” said Van Triest. “You’ll have a lot of headwinds. You will stay north and have to deal with three fronts at least – three low pressure systems – and then, at the end, you will be hoping for the Bermuda replacement high to move in and give you a get-out-of-jail card and come down south on a fast angle.”

We put Van Triest on the spot. If he was talking to a team right now, which one would he go for – more pain in the north or an easier time of it down south? “I would go north,”he said, “because to me, it feels wrong to put all the chips on the table (so early) in the race and try to break through in the south. You don’t know if you’re going to get through and, once you’ve got through it won’t be like you’ve won the jackpot – that will only be the case if the northerly route doesn’t work. And psychologically that’s a difficult thing to do.”

He likes the north because it offers more options and navigators will be able to work with the weather more effectively. “On the northerly option, you’ve got a lot more control over your destiny,” said Van Triest. “People say ‘it’s going to be really windy,’ but you don’t have to do that – you can go further south, right? You don’t have to take the optimum route – you can put the cursor where you want.”

His final summation: “You could take the southerly route because it will be at optimum performance for the boats’ polars and because it will be benign conditions, it will be warmer and nicer for the sailors. But, at this stage, I would say the winning boat will come out of the north…”

However, Van Triest underlines that this is very early stages in a changing picture that is more erratic than usual. “What is important to keep in mind is that the weather systems are what we call progressive, as opposed to stationary,” he said. “Everything is moving at pace, all the weather is coming through really quickly, so there will be things happening and there will be opportunities. You know, you need to come down south at the right time. It’s not like you’re into some sort of static situation that you can’t get out of – there’s new weather arriving from the west all the time.”

Once in the tradewinds, van Triest says they are likely to be medium strength – 15-20 knots – but also variable in strength because of the poor establishment of the high pressure system to the north. “Everything is moving through really quickly, so there are periods of decent trades, but then it goes light again,”he summarised.

Ed Gorman

Teams info

THE LIST OF 40 SKIPPERS UNVEILED

The 2020 edition of the Vendée Globe has generated unprecedented interest. As a result, the organisers decided to increase the number of places at the start to 40 for the 2024 edition. 44 skippers applied for this 10th e…

•••Charlie Dalin: The podium in IMOCA is much harder to reach now

Charlie Dalin has particularly enjoyed his convincing win in the New York Vendée-Les Sables d’Olonne race. And that’s partly because he knows that even getting on the podium in the IMOCA Class is becoming more difficult.

•••