The explosive increase in IMOCA performance – the numbers tell a spectacular story of innovation

Anyone who has followed the growth of the IMOCA Class in recent years will be well aware that the boats are now going faster than ever before and that the advent of foils has produced a spectacular jump in performance.

While the skippers are well aware of the increase in speeds, and the ability of the latest boats to convert ever lower true wind speeds into ever-increasing boatspeed, there has been little published work on this subject to help those following the Class understand exactly what has been going on.

But now the French sailor and performance expert Olivier Douillard, whose company AIM45 specialises in data analysis and data management and works with many IMOCA teams, has completed a study that clearly shows the breathtaking changes over the last 20 years in the way IMOCAs perform.

Using polar data and performance data from the best boats in the fleet through each Vendée Globe boat generation, Douillard has studied the way IMOCAs have been sailing over 20 years starting from 2002. This is a period when boats have gone from daggerboards to canting keels and then the advent of foils in 2016 which, along with hull designs, have been steadily refined since then.

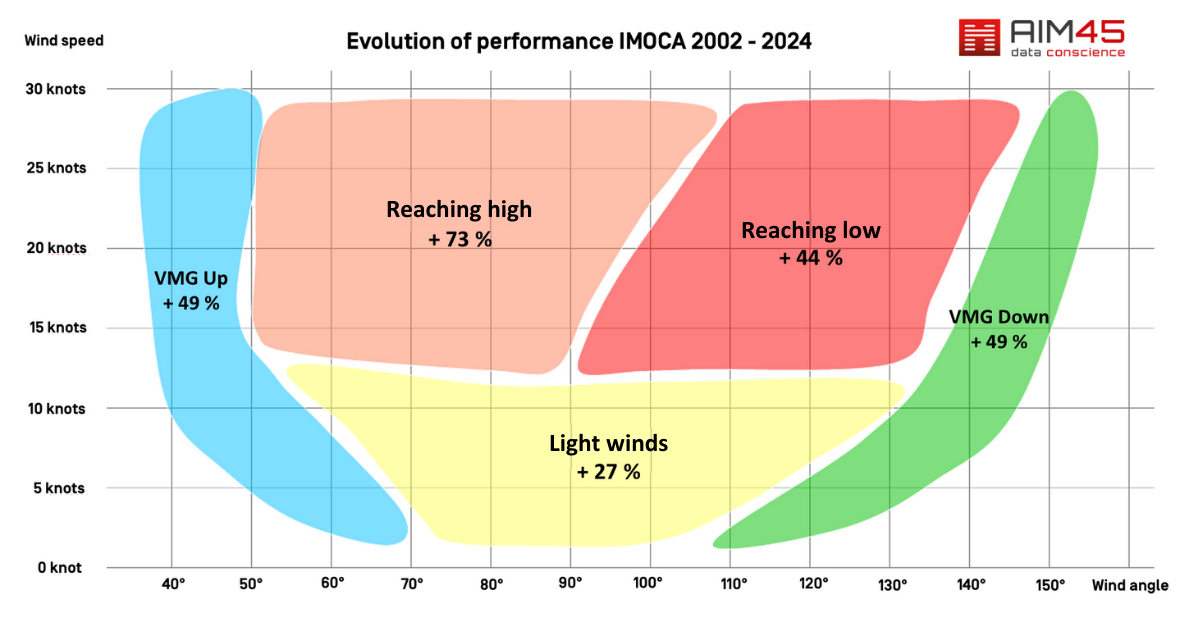

His analysis shows that performance overall has increased by 48% depending on the point, or mode, of sailing, a remarkable jump. He has also shown how the wind strength required to reach 20 knots of boatspeed has fallen from 30 knots 20 years ago, to just 14 knots today. Again, a remarkable transformation in what an eight-tonne IMOCA yacht is capable of doing.

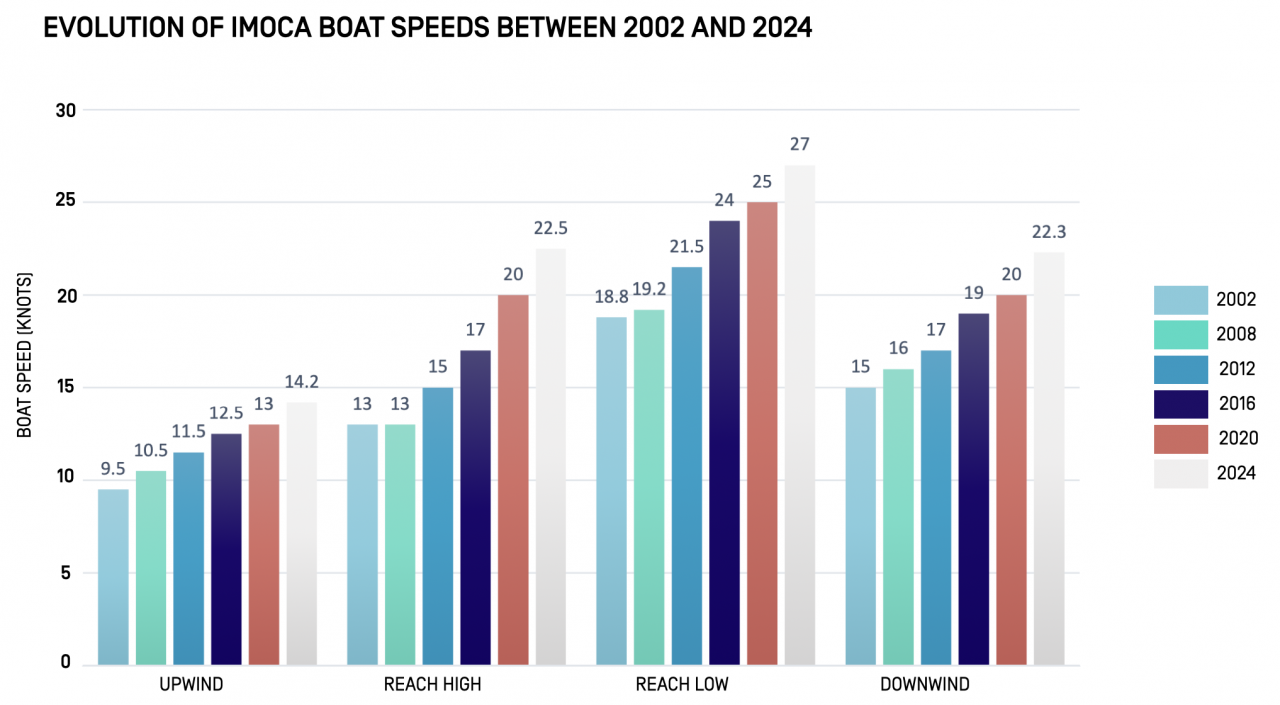

Breaking it down into the different points of sail, Douillard’s study shows that going upwind, the best IMOCAs are now travelling 49% faster than they were in 2002, from nine knots to 14 knots of boatspeed, using a common measurement of upwind speed (VMG); in light winds the performance increase is of the order of 27%, from just under nine knots to 11 knots; downwind there is a 49% increase, from 15 to 24 knots.

The most spectacular numbers are in high reaching mode, when the wind is coming from the side of the boats. In this mode, the latest foilers are achieving speeds that are 73% faster than they were 20 years ago, jumping from 13 knots to 22 knots of boatspeed. Then, when low reaching (around 120° to the wind), the increase is 44%, with speeds that can exceed 27 knots, which is clearly the fastest point of sail.

Speaking this week, as the Class prepares for the Transat Jacques Vabre Normandie Le Havre, Douillard says he is not surprised by what the data is revealing. “I’m not completely surprised but, for sure, it is a bit shocking – you are looking back over 20 years and you see the increase in performance is not a small step, it is a big one,”he said.

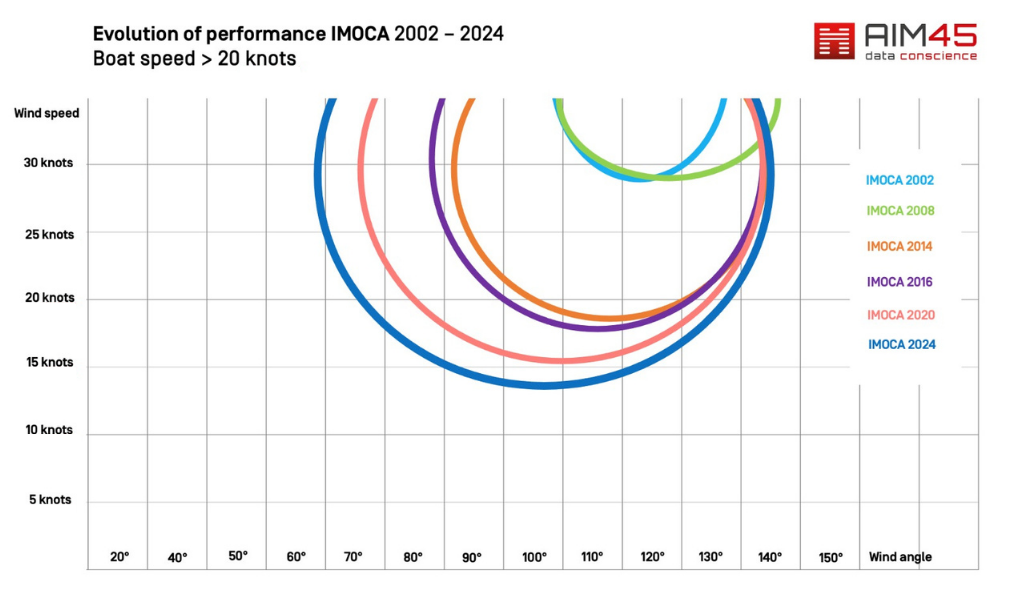

The research on windspeed required to achieve boatspeed of 20 knots shows that, up to 2008, IMOCAs required 30 knots of true wind to achieve that speed. This had fallen to 18 knots by 2016 with the introduction of foils. Since then, the windspeed required has steadily dropped as foils have become more efficient and refined, with the current true wind figure for 30 knots of boatspeed sitting at an improbable 14 knots.

Overall, Douillard believes the rate of increase in speeds has probably peaked unless radical changes are made to the Class rule, for example allowing T-foils on the rudders which are currently not permitted.

“This big increase in performance since 2002 has come from a major modification of the boats with the introduction of foils,” explained Douillard. “So to get a new step like this, you would need another new configuration that would push performance much higher. Otherwise it will increase incrementally because the sailors learn and adjust many small things. But it will not be a new big step.”

He believes one of the keys to continuing increases in performance will be the ability of skippers to sail their boats in a fast but stable manner. “If the rule doesn’t change, the learning curve about stability will allow performance to increase, but less dramatically,” he said. “It will be slowly, slowly but it will really also depend on the skipper and the way he will trim the boat for long periods that will make a lot of difference.”

Ed Gorman

Teams info

The Transat CIC: a spectacular start!

Brittany turned on its best Spring sailing weather – sunshine, puffy cumulus clouds and a decent 10-15kts of Westerly wind – to send the 48 strong Transat CIC fleet on its way from Lorient towards New York for the start …

•••Charlie Dalin: Raring to go on his first solo The Transat CIC

It’s good to see Charlie Dalin back where he belongs, at the helm of his almost brand new Guillaume Verdier IMOCA, Macif Santé Prévoyance, ready to take on the north Atlantic in The Transat CIC.

•••